In English, there is something called a “poster child.” Originally, the phrase “poster child” came from when a child in pain was put on a poster to help raise money for a cure to a disease; nowadays, a poster child is used to describe any person who is used to promote a cause. As a simple example, during the 2008 presidential elections, Obama was called a “poster child” because he was a regarded as evidence that America had moved past racial discrimination.

In English, there is something called a “poster child.” Originally, the phrase “poster child” came from when a child in pain was put on a poster to help raise money for a cure to a disease; nowadays, a poster child is used to describe any person who is used to promote a cause. As a simple example, during the 2008 presidential elections, Obama was called a “poster child” because he was a regarded as evidence that America had moved past racial discrimination.

Nadine Labaki of Lebanon, after international and sensational reviews of her 2007 movie Caramel, is said to be the poster child of the Middle East. She is an incredible woman in the Middle East. People may have thought that by praising this woman, they could show concern for issues of Middle Eastern women.

Obama has successfully guided America by way of four years of political achievements. He bravely addressed difficult issues that many in America wished to see resolved such as nationwide health insurance, the legalization of same-sex marriage, and the stabilization of international relations. Not many people nowadays would say that they either support or hate Obama because he is black. At least I haven’t met these kind of people. Because of his achievements, Obama is respected as a human. Now, after four years, Obama is no longer a poster child.

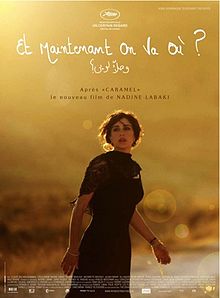

Alternatively, what about Nadine Labaki? Her maiden’s work Caramel is the bittersweet perspective of women’s stories of passion and love. It is an undeniably pleasant movie. Her challenge was where she could go with her second work. Her second piece Where Do We Go Now? depicts the religious antagonism of Lebanon.

Five years after her first movie, Nadine Labaki appeared in an interview after the filming of her second movie, radiantly beautiful as before. However, in five years, there was a very important change in her. She had married composer Khaled Mouzanar and become a mother, and she was full of the confidence of a woman and of a mother. “Lebanon was in pieces from the war. I made this movie to ask whether mothers can protect their children from being taken away to war,” she said.

One more difference was that her English had improved significantly. In her interview for Caramel, she spoke in broken English and seemed frustrated that she could not speak as fluently as if she were talking in Arabic or French. By this interview five years later, though, she was able to converse quite fluently. She talked 10 times or even 100 times more when presented with a question. Without Labaki’s permission, her husband Khaled Mouzanar suddenly snatched the microphone from her, saying condescendingly, “I’m sorry, my wife is a little too talkative. Moreover, somewhat schizophrenic.”

The criticism of her husband about her being “too talkative and schizophrenic” unexpectedly summarizes the shortcomings of Where Do We Go Now?. The theme in this movie is that, when men might become violent because of religious conflict, the women can use their wit to try to prevent it. The chattering of women continues through the chaos as various people appear one after another, making it hard to follow the characters; somehow romance happens, and the women bring Ukrainian dancers to the village to keep the men’s eyes from violence. The boring story digresses and keeps going on and on. When the movie is close to the end, it seems as if the director thought, “Shoot! I have to wrap it up!” The women (Christian and Muslim women on good terms) hurriedly feed the men cake with hashish (cannabis), and, while the men sleep, the women secretly hide the weapons in a hole. The women at the end of the movie hope that the violence will not happen for a while. “The women are the ones who have to grieve and bury their loved ones after the men fight” is the message of this movie. The movie was a mix of drama, tragedy, comedy, and even musical.

The criticism of her husband about her being “too talkative and schizophrenic” unexpectedly summarizes the shortcomings of Where Do We Go Now?. The theme in this movie is that, when men might become violent because of religious conflict, the women can use their wit to try to prevent it. The chattering of women continues through the chaos as various people appear one after another, making it hard to follow the characters; somehow romance happens, and the women bring Ukrainian dancers to the village to keep the men’s eyes from violence. The boring story digresses and keeps going on and on. When the movie is close to the end, it seems as if the director thought, “Shoot! I have to wrap it up!” The women (Christian and Muslim women on good terms) hurriedly feed the men cake with hashish (cannabis), and, while the men sleep, the women secretly hide the weapons in a hole. The women at the end of the movie hope that the violence will not happen for a while. “The women are the ones who have to grieve and bury their loved ones after the men fight” is the message of this movie. The movie was a mix of drama, tragedy, comedy, and even musical.

The theme is that the women conspire to keep the men from war, like the Ancient Greek comedy, Lysistrata. In fact, many movie critics discuss this movie in comparison with Lysistrata. Nadine Labaki said that she didn’t actually have this Greek comedy in mind, and I think this is true. I think it was a natural result of Labaki’s character when making a movie with the theme of war.

Her talent or perhaps her spirit shines fully with Caramel, where the chatter jumps among the women endlessly, but perhaps serious themes like war and religious opposition don’t suit her well. Furthermore, she doesn’t really seem to be interested in those kinds of themes. Political themes are not exactly her cup of tea. To put it most simply, this movie wants to say, “If each woman can suppress the aggression of her husband and children, who knows? Maybe we can get rid of war from this world.” At first glance, this movie seems to take the stance that war can possibly be stopped by women opposing it and that though it may be difficult, it’s worth trying. But this is not the case. This difference draws the criticism that this movie does not offer a solution. No one has a clear solution for the future direction of Lebanon. This criticism from some viewers stems from their realization of the director’s limitations with this subject. This movie is light like Caramel. This lightness is due to Labaki’s personality, for better or for worse, and not due to any restrictions by the government.

When an interviewer said, “Your song and dance in the movie was really beautiful,” she replied, modest as always, “I’m not good at singing.” Her dance is not so much of a dance nor is it artistic as she moves her body lightly. At this point, her husband who was in charge of the music of the movie, again abruptly snatched the mic and said, “I don’t like her voice, so I insisted that we find someone to dub over her. We did a lot of auditions for a woman singer, but she wasn’t satisfied with any of them and decided to use her own voice. But I had a lot of difficulty and had to use a lot of acoustic tricks so that her voice didn’t sound funny.” To which she seemed to say with her face, “You shouldn’t have exposed so much.” After hearing this, I worried, “I hope they didn’t fight over this later.”

After finishing watching this movie, I honestly wasn’t able to shake the feeling that Nadine Labaki is still a poster child. However, it isn’t that she doesn’t have talent. She is the sole renowned female director and top actress in the extremely weak film world of Lebanon. Having become such an important woman in a single swoop, it may be difficult now to take honest criticism. But I hope she listens to these critiques, gives young people opportunities, and contributes to the development of the film industry of Lebanon.