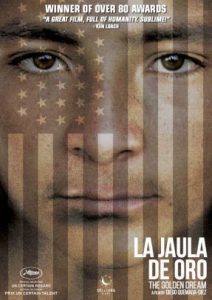

This Mexican film is a very powerful and sad movie, full of both beautiful images and heartbreaking realities. It is a story of four kids who venture on the long and dangerous journey from Guatemala to the U.S.—the land of the free and of opportunity—in hopes of a better life. Even though this movie is fiction, a similar story is sadly true for countless people who risk their lives trying to escape their dangerous country—be it Guatemala, Venezuela, Ukraine, Burma, Syria… This is another entry that I started a while ago that got harder for me to finish as the content only got more relevant to the situation in our country.

This Mexican film is a very powerful and sad movie, full of both beautiful images and heartbreaking realities. It is a story of four kids who venture on the long and dangerous journey from Guatemala to the U.S.—the land of the free and of opportunity—in hopes of a better life. Even though this movie is fiction, a similar story is sadly true for countless people who risk their lives trying to escape their dangerous country—be it Guatemala, Venezuela, Ukraine, Burma, Syria… This is another entry that I started a while ago that got harder for me to finish as the content only got more relevant to the situation in our country.

The movie starts with one of the kids, Sara, cutting her hair (to pass as a boy), packing her few possessions and money, and walking through the poverty-stricken streets with her other two friends. As they set off, it is clear that they are not leaving much behind (they don’t appear to even have any family who would notice their absence). The kids seem to have a romantic feeling that, as they leap into the unknown with nothing to lose, things could only get better for them. Throughout their journey, there are small sweet moments of hope. People alongside the train tracks throw fruit to the weary travelers on the train and wish them good luck; they encounter a kind farmer and a priest who feed the children and let them stay in their homes;  or when they first arrive in Mexico (early enough when the children are still optimistic and it feels almost like a fun adventure as tourists), the kids treat themselves to some snacks and take silly photos together. But then they lose everything they have—several times—on their journey. It’s horrible that people take advantage of and steal from vulnerable people who are already have so close to nothing.

or when they first arrive in Mexico (early enough when the children are still optimistic and it feels almost like a fun adventure as tourists), the kids treat themselves to some snacks and take silly photos together. But then they lose everything they have—several times—on their journey. It’s horrible that people take advantage of and steal from vulnerable people who are already have so close to nothing.

This movie also depicts the discrimination against the indigenous population that is still present in Mexico and Guatemala. On their journey, the friends meet Chauk, a native Mayan boy who speaks his native language instead of Spanish, so there is a language barrier. Initially, Juan is very rude to Chauk, calling him a “primitive Indian” and telling him he can’t travel with them (even though he is a boy of a similar age and all alone on the long journey to the U.S!), but Sara is nicer to Chauk and finds ways to communicate despite the language barrier.  Juan’s upsetting behavior shows how culturally deep prejudices towards indigenous groups can run in people from more urban settings and alludes to the long history of violence and oppression toward indigenous people. Eventually, Chauk “proves himself” to Juan by having useful skills such as knowing how to kill a chicken for food or using natural remedies to help Juan when he is injured. This movie gently reminds us of the diversity of the “Hispanics” hoping to cross into our country.

Juan’s upsetting behavior shows how culturally deep prejudices towards indigenous groups can run in people from more urban settings and alludes to the long history of violence and oppression toward indigenous people. Eventually, Chauk “proves himself” to Juan by having useful skills such as knowing how to kill a chicken for food or using natural remedies to help Juan when he is injured. This movie gently reminds us of the diversity of the “Hispanics” hoping to cross into our country.

This is definitely not a Hollywood movie, and I imagine it may not sit well with many U.S. audiences. There are no happy endings for anyone. (If you care, the rest of the paragraph is a spoiler). Their friend Samuel gives up and turns back at the Guatemala-Mexico border after they lose all of their possessions. Sara gets taken away by ruthless men when they realize she is a girl instead of a boy.  In a Hollywood movie, there probably would have been an incredible and serendipitous reunion with Samuel down the road and a dramatic rescue mission to save Sara. But in reality, all of the characters are helpless and have no resources. When Sara is taken away, they have no way of knowing where she was taken or what happens to her. Barely hanging onto life themselves, there is nothing they can do except try to continue onward towards the U.S. border. Chauk is killed at the border by Border Patrol and that is the end of his story. In Hollywood, this movie might have been some touching coming-of-age story. It is true that the kids have to learn a lot living on the road, experiencing new things and learning some dark realities. But there is no rosy achievement of adulthood or caring mentor for these youths. Characters are gone and the movie just moves on.

In a Hollywood movie, there probably would have been an incredible and serendipitous reunion with Samuel down the road and a dramatic rescue mission to save Sara. But in reality, all of the characters are helpless and have no resources. When Sara is taken away, they have no way of knowing where she was taken or what happens to her. Barely hanging onto life themselves, there is nothing they can do except try to continue onward towards the U.S. border. Chauk is killed at the border by Border Patrol and that is the end of his story. In Hollywood, this movie might have been some touching coming-of-age story. It is true that the kids have to learn a lot living on the road, experiencing new things and learning some dark realities. But there is no rosy achievement of adulthood or caring mentor for these youths. Characters are gone and the movie just moves on.

The cinematography of this film is attractive. There is not much dialogue in the film and many scenes are filmed with a “rough documentary” style, with a shaky camera that is often very close to the characters. Many scenes show the vast landscapes of Mexico on the train, crossing bridges and through deserts. Imagery of snow is seen throughout the movie. At first, there is wonder and still some optimism in their eyes. In the last scene, though, the snow feels very lonely.

The cinematography of this film is attractive. There is not much dialogue in the film and many scenes are filmed with a “rough documentary” style, with a shaky camera that is often very close to the characters. Many scenes show the vast landscapes of Mexico on the train, crossing bridges and through deserts. Imagery of snow is seen throughout the movie. At first, there is wonder and still some optimism in their eyes. In the last scene, though, the snow feels very lonely.

The last scene is very powerful. Juan, after everything he has been through, has made it to the U.S. We see him working in a meat factory in an oversized uniform (he is probably not even old enough to be allowed to work in such an environment), covered in blood, shoveling up pieces of meat and fat.  Other immigrants work the line, hacking away at chunks of cow, working through mountains of meat, packaging the meat, and injecting it with preservatives. (Side note: This is the ugly reality of the meat industry that supports our diet filled with meat in the U.S.). These are the kind of jobs “immigrants are taking away from Americans”—jobs that no American wants. These are the inglorious opportunities that await someone who may have risked their life to get here. This is the exploitation of a vulnerable population that has to work for low wages, since undocumented individuals constantly have to live in fear of being deported and replaced by someone else. This is the reality of the American Dream for many.

Other immigrants work the line, hacking away at chunks of cow, working through mountains of meat, packaging the meat, and injecting it with preservatives. (Side note: This is the ugly reality of the meat industry that supports our diet filled with meat in the U.S.). These are the kind of jobs “immigrants are taking away from Americans”—jobs that no American wants. These are the inglorious opportunities that await someone who may have risked their life to get here. This is the exploitation of a vulnerable population that has to work for low wages, since undocumented individuals constantly have to live in fear of being deported and replaced by someone else. This is the reality of the American Dream for many.

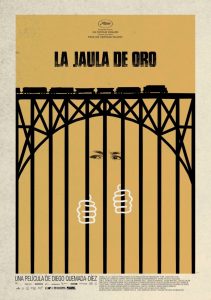

The title directly translates as “the golden cage.” This is apt to describe their home country of Guatemala, beautiful but with limited opportunities and people work tirelessly to escape.  “The golden cage” also describes the U.S. The U.S. is supposed to be a golden land of opportunity, but in reality, an undocumented immigrant such as Juan has limited and grim options. Many people have left their home and family behind in hopes of safety and work here in the U.S. In the Mexican song with the same title La Jaula de Oro, there is a line that translates to: “I have my wife and children whom I brought when they were young. They’ve already forgotten my beloved Mexico, which I will never forget and to which I can never return. What good is money if I am like a prisoner in this great nation?”

“The golden cage” also describes the U.S. The U.S. is supposed to be a golden land of opportunity, but in reality, an undocumented immigrant such as Juan has limited and grim options. Many people have left their home and family behind in hopes of safety and work here in the U.S. In the Mexican song with the same title La Jaula de Oro, there is a line that translates to: “I have my wife and children whom I brought when they were young. They’ve already forgotten my beloved Mexico, which I will never forget and to which I can never return. What good is money if I am like a prisoner in this great nation?”

To understand why so many people are trying to flee Central America and seek asylum in the United States, we need to look at the long history of violence and dictatorships, and the role the U.S. played in this.

We will start in El Salvador. The Salvadoran Civil War between the military-led government and a coalition of left-wing groups (FMLN) started in 1979 and continued until 1992. For much of the 20th century, El Salvador saw growing socioeconomic inequality and electoral fraud, resulting in increased unrest and activity of populist groups. Fearing a communist takeover, the U.S. administration, starting with President Carter and continuing with Reagan and George H.W. Bush, contributed around 4 billion dollars of aid that helped maintain the Salvadoran military dictatorship. The U.S. support was influential in tipping the Salvadoran Presidential elections in 1984 and 1988 to maintain the military rule. By the end of the Civil War, over 70,000 civilians died and over a million more were displaced from their homes. The government carried out targeted assassinations of human rights advocates, leftist activists, and religious figures providing humanitarian relief. There were also indiscriminate massacres like the one in El Mozote, where nearly 1000 civilians including women and children were tortured and killed; the U.S. covered up the existence and repressed media coverage of this event. Finally, with the Cold War drawing to a close and after over a decade of back-and-forth violence, peace negotiations began and the Chapultepec Peace Accords were signed in 1992.

During this violence and instability, many Salvadorans, displaced by the violence in their country, came to the U.S. Most of them, however, were not granted asylum due to a disproportionately low approval rate for Central Americans. Many of these “illegal immigrants” ended up in Los Angeles. There we have the birth of MS-13. MS-13 began as a brotherhood among young Salvadorans during a time when they were strongly discriminated against. Unfortunately, this morphed into something much more violent, escalated by other gang presence in LA.

In the 1990s, many gang members were arrested and deported back to El Salvador, which was recovering from a (U.S.-funded) civil war. El Salvador had a broken police force, an unstable economy and high unemployment, and a dangerous amount of leftover firearms. In an attempt to reduce gang violence, the Salvadoran government granted amnesty or lighter sentences to convicted members in exchange for surrendered firearms, but this resulted in the opportunity for the gang to organize, recruit, and expand. Consequently, a gang presence and gang-related violence has spread throughout Guatemala and Honduras, susceptible due to their own political and socioeconomic instability.

From 1960-1996, Guatemala was dealing with its own, longer civil war. By the turn of the 20th century, Guatemala was a quintessential banana republic: under authoritarian rule that served U.S. corporate interests, namely the United Fruit Company. In addition to major tax exemptions for corporations, the government passed legislation that took land away from the native population in Guatemala and essentially trapped them in indentured servitude to the new landowners. The United Fruit Company particularly benefited from these exploitative labor laws and the new land gifted to them. By the 1930s, under the particularly repressive regime of Jorge Ubico—who self-identified as a fascist, admired leaders like Hitler, and was backed by the U.S. government—social unrest was mounting and labor unions and farmers (primarily indigenous Mayan) were actively protesting. After a popular uprising, Guatemala reached a moment of relative stability and had two consecutive fairly and democratically elected Presidents: Arévalo and Árbenz.

Arévalo implemented minimum wage laws, greatly expanded voting rights, and increased funding for education. Árbenz continued this legacy and went a step further by implementing land reform. At this time, 70% of the land was owned by 2% of the population in Guatemala; Árbenz’s reform took uncultivated land plots from these large landowners/corporations and distributed them to over 500,000 poor and landless peasants (primarily indigenous) to be able to become productive farmers. The Red Scare in full force, the U.S. viewed this land reform as communism; President Truman started the motions while Eisenhower was the one to fully authorize the CIA to spread anti-Árbenz propaganda and organize a coup to remove Árbenz in 1954. Not coincidentally, members of Eisenhower’s administration had major investments in the United Fruit Company, which was very unhappy with some favorable legislations being reversed.

For four decades, the U.S. government continued to support a series of military dictatorships through millions of dollars of military aid and using the CIA to train paramilitary death-squads in Guatemala. The Guatemalan government targeted and tortured any suspected enemies of the state, censored the press, and reversed many of the democratic reforms of Arévalo and Árbenz—once again taking land away from small farmers and eliminating democratic elections. One of the dictators even stated, “If it is necessary to turn the country into a cemetery in order to pacify it, I will not hesitate to do so.” Around 1980, violent rebellion from armed leftist guerilla groups peaked; in response, the government cracked down more and authorized a widespread genocide of hundreds of rural Mayan communities for suspected sympathy to the cause. By the end of the Guatemalan Civil War, nearly 200,000 people died and a million more were displaced, many of which were indigenous people.

Finally in 1996, the U.N. negotiated the peace accords, intervening due to the atrocities especially committed against the indigenous Mayan population. Some of the guerilla fighters received land in exchange for disarming. The country has been rebuilding since, but there is still lots of crime, corruption, and poverty. All of this has made the country susceptible to the expansion of the gangs such as MS-13 since the 1990s.The U.S. also established a military presence in Honduras in the 1980s to provide extra support for the military dictatorship in El Salvador and suppress rising leftist groups in Honduras. While spared a full-on civil war like its neighbors, Honduras today still struggles with economic disparity, crime, and sexual violence. As recently as 2009, Honduras had a military coup, which has reduced political stability and reversed progress made on the issues of poverty and unemployment.

Today, the U.S. continues to remain very involved with affairs in Central and South America. In particular, Venezuela is currently an extremely unstable authoritarian state that was built on its large oil reserves; it is clear things cannot continue as they are for the people of Venezuela. The U.S. recently appointed Elliot Abrams—who advocated to aid the military dictatorships in both Guatemala and El Salvador and denied many of the acts of violence committed by the governments during their respective civil wars—as the Special Representative for Venezuela. I fear how the U.S. might choose to intervene and use the disarray of the so-called socialist state of Venezuela as an example. All eyes are on how the world will intervene with Venezuela.

A print produced by a revolutionary art group in Mexico. It graphically depicts how people die on the journey to the United States. It also criticizes how we dehumanize people to simply which foreign country they are coming from.

I spent a month at the U.S.-Mexico border, where every day hundreds of families (mainly Guatemalan, Salvadoran, or Honduran) crossed and legally submitted themselves to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in hopes of being granted asylum from the (U.S.-supported) instability and violence of their home countries. Many were young parents traveling with their children. Despite everything these families had gone through, they often lost their few possessions, either to the disingenuous people they had paid to help them reach the border or during ICE custody. Many of the families from Guatemala were indigenous Mayan, speaking one of the many native Mayan languages in addition to Spanish.

The continued demonization of a whole region of people and cruel policies such as separating families at the border has done little to reduce border crossings, nor activity of gangs such as MS-13. In La Jaula de Oro, there are heartbreaking scenes where immigrants are hunted and shot down by snipers. The movie also depicts more realistically what these supposed “caravans of criminals” really are: a group of weary travelers, young and old, on a train or often just walking by foot, with little more than the clothes on their backs, hoping for a place to call home. As the debate in the U.S. continues about border security and keeping out the “bad hombres” invading our country, perhaps we will successfully reduce immigration by killing the idea of the American Dream and the image of the U.S. being the Land of Opportunity for all people.