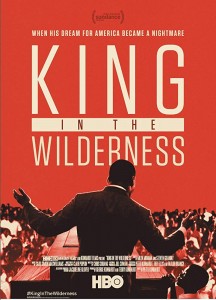

This entry is about a recent documentary that focuses on Martin Luther King Jr’s final years. There was a distinct shift in the mid 60s as King expanded his efforts against poverty and violence. This pulled King in many directions and unfortunately made him some enemies. This documentary was released on HBO on April 2, 2018 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the death of King. This documentary weaves together original footage of King’s speeches with modern interviews of some of his close friends reflecting back on the days they worked alongside King. This entry piggy-backs off of my entry about the historical drama film Selma.

This entry is about a recent documentary that focuses on Martin Luther King Jr’s final years. There was a distinct shift in the mid 60s as King expanded his efforts against poverty and violence. This pulled King in many directions and unfortunately made him some enemies. This documentary was released on HBO on April 2, 2018 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the death of King. This documentary weaves together original footage of King’s speeches with modern interviews of some of his close friends reflecting back on the days they worked alongside King. This entry piggy-backs off of my entry about the historical drama film Selma.

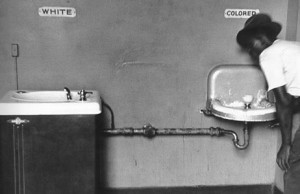

The timeline in this documentary starts in 1966 when King went to live in a run-down building in Chicago. This was the beginning of his movement to End Slums in Chicago. With all the attention on demonstrations in the South, there was a common sentiment that a place in the North like Chicago didn’t have race issues. However, the dilapidated building infested with rats and sometimes lacking heat or electricity that King stayed in was not uncommon in Chicago; King was calling attention to the poor housing conditions and interrelated lack of access to education and employment in these poor and predominantly black neighborhoods in the West Side of Chicago. King patiently marched and organized community leaders to demand that folks should not be denied decent housing because of the color of their skin. King said the strong resistance he faced in Chicago by white folks showed the true colors of the U.S. Slums like the one he was staying in were being created and upheld by the system. In one speech in Chicago, King said point-blank, “We are tired of being lynched physically in Mississippi, and we are tired of being lynched spiritually and economically in the North.”

The timeline in this documentary starts in 1966 when King went to live in a run-down building in Chicago. This was the beginning of his movement to End Slums in Chicago. With all the attention on demonstrations in the South, there was a common sentiment that a place in the North like Chicago didn’t have race issues. However, the dilapidated building infested with rats and sometimes lacking heat or electricity that King stayed in was not uncommon in Chicago; King was calling attention to the poor housing conditions and interrelated lack of access to education and employment in these poor and predominantly black neighborhoods in the West Side of Chicago. King patiently marched and organized community leaders to demand that folks should not be denied decent housing because of the color of their skin. King said the strong resistance he faced in Chicago by white folks showed the true colors of the U.S. Slums like the one he was staying in were being created and upheld by the system. In one speech in Chicago, King said point-blank, “We are tired of being lynched physically in Mississippi, and we are tired of being lynched spiritually and economically in the North.”

King faced many angry and violent protesters (seen in the footage holding signs like, “We Want Wallace”), yet was always resolute with his commitment to nonviolent resistance. King was calling for a restructuring of society and said this movement, “might be the biggest thing since our march in Selma.” As the third largest city in the U.S., he figured if the problems in Chicago could be solved, these problems could be solved everywhere.  In contrast to the amicable relationship between President Johnson and King seen in Selma a few years prior, here we hear conversations between Johnson and Robert Daly (the mayor of Chicago at the time) about how to “handle King.” Since the march on Selma, President Johnson and his administration felt that King was overstepping with his demands. This only worsened when King later spoke out against the Vietnam War.

In contrast to the amicable relationship between President Johnson and King seen in Selma a few years prior, here we hear conversations between Johnson and Robert Daly (the mayor of Chicago at the time) about how to “handle King.” Since the march on Selma, President Johnson and his administration felt that King was overstepping with his demands. This only worsened when King later spoke out against the Vietnam War.

For a while, King–as advised by his close friends–refrained from publicly taking a stand against the Vietnam War. People on his staff were wary about him getting involved in other movements because they felt he was biting off more than he could chew, and some of the protests against the Vietnam War were violent and disorganized. In addition, speaking out against the war was seen as anti-American and adversarial towards President Johnson, an ally in the Civil Rights Movement. King and his associates were already being closely surveilled by the FBI, so they feared that speaking out against this war alongside his essentially socialist empowerment of working-class people would be flagged as Communist amidst a Red Scare.

Coretta Scott King was actually vocal against the Vietnam War first, joining in some protests without her husband. Martin Luther King Jr. kept some distance from the movement, but anti-war groups continued to request his support. As an advocate for nonviolence and for all people, King felt he could not in good conscience remain silent on the war. In 1967, King gave a powerful speech at the Riverside Church where he said that he could no longer speak out against the violence and injustice within his country without also speaking out against the violence his country—“the greatest purveyor of violence in the world”—was responsible for abroad. His speech against the Vietnam War highlights the interrelatedness of everything he fought against. Poor men–disproportionately people of color–with no other choice were sent abroad and died for a country that wasn’t supporting their communities or their own liberties. King argued that these issues are all related in his movement for peace.

After this speech, the media and even some of his allies turned on him, saying things like he had “no right having an opinion on foreign affairs,” or questioned his audacity to speak out against “issues beyond civil rights.” King is rightfully celebrated for his fight against segregation and racism, but when he founded the Poor People’s Campaign and supported anti-Vietnam War protests, some people felt he was rocking too many boats. In this documentary, his friends recalled somberly how heavily the betrayal weighed on King when those around him did not support him in this decision.

Meanwhile, King was also trying to manage a significant split that was happening within the Civil Rights Movement. Stokely Carmichael, head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and a participant in the march from Selma, felt strongly that the key was to empower Black Power to fight back. To him and a growing number of black activists, nonviolence was a tactic appropriate for some situations, but fighting back meant using violence if needed to get change.  King always advocated for only nonviolent protests, but he understood that people were frustrated. He supported the protests led by Carmichael and marched alongside him in hopes that he could keep them nonviolent. As the Black Power movement gained momentum, though, King was left trying to manage this fire among all the others.

King always advocated for only nonviolent protests, but he understood that people were frustrated. He supported the protests led by Carmichael and marched alongside him in hopes that he could keep them nonviolent. As the Black Power movement gained momentum, though, King was left trying to manage this fire among all the others.

This divide that was happening 50 years ago is still very relevant to the social justice movement today. In his famous letter from the Birmingham Jail, King said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” King tirelessly fought against injustice, and he knew that the fight against racism, poverty, and war were all connected. Despite knowing that he was being spread too thin, he could not turn his back on any of these fights. Carmichael, on the other hand, believed that it was not actually possible for black people to gain power within a system made by white people. While he agreed that racism and poverty were deeply connected, he felt that rising to middle class meant assimilating into the “white world” and then turning your back on your brothers. The fear that, after helping your brothers up, they will immediately pull the ladder up behind them and leave you to suffer is common and understandable, but has always splintered working-class movements. King’s Poor People’s Campaign was a very intentional effort to unite all working-class folks, regardless of their color or background, through their shared desire for improved living conditions.

Martin Luther King Jr. was truly an inspirational leader, full of compassion and always committed to nonviolence. Even when someone threatened his life, King had no hate for them and continued to believe that all people are on the same side. He viewed racism like a sickness and preached that we mustn’t blame the sick, but try to cure the sickness. In this film, his friends talk about how he did not fear death, and even used humor to address the reality that the nature of his work would likely eventually kill him. King beautifully said, “If you truly want to be free, you must get over the love of wealth and the fear of death.”

This film includes some footage from King’s funeral. Coretta is seen standing stoically at the funeral, which was open-casket and open to the public. It must have been very hard for the family to have to mourn publicly, but Coretta knew that his death was hard on everyone and that the people needed this funeral as a chance to mourn as well. There is a heart-wrenching moment when Martin Luther King Sr. is overcome with grief when he looks at his son’s casket.

This film includes some footage from King’s funeral. Coretta is seen standing stoically at the funeral, which was open-casket and open to the public. It must have been very hard for the family to have to mourn publicly, but Coretta knew that his death was hard on everyone and that the people needed this funeral as a chance to mourn as well. There is a heart-wrenching moment when Martin Luther King Sr. is overcome with grief when he looks at his son’s casket.

A commemoration like this film is a good reminder of the progress we have made and how much more work needs to be done here in the U.S. I am so thankful of the progress made due to the fearless struggles by those before us and continued by people today. I attended a service at a Baptist church near me that was also in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of King’s death. The service featured three members of the church who had participated in the March on Washington. One woman talked about how she, in her twenties at the time, had marched alongside an 82-year-old woman who marched with such enthusiasm because of how important that moment was to her. Both of them looked at all the people gathered around them and were filled with hope. Reflecting back during this service, this woman was also grateful for all the progress that had been made in the past 50 years. I hope many more leaders carrying the mantle of nonviolent struggle against racism, poverty, and imperialism arise.