This movie is very difficult to understand. The original work was literature that praised the leader of the communist party, and it was approved by the Communist Party of Poland; but in the movie adaptation, director Andrzej Wajda made the communist party leader protagonist into a supporting role, and made a young guerilla planning an assassination—who had just a minor role in the original work—the protagonist in the movie. This protagonist is a freewheeling and unattached young man with weird-looking glasses. He falls in love with the girl at a bar—who is like a diamond in the ash—and they understand each other’s circumstances of their families being massacred by German soldiers; with this, he begins to transform—once he takes off his glasses—into a lonely handsome man resembling James Dean. I think the reason this movie is hard to understand is that the political situation at that time was complicated, and in order to pass censorship, the movie minimizes conversation and uses many metaphors.

This movie is very difficult to understand. The original work was literature that praised the leader of the communist party, and it was approved by the Communist Party of Poland; but in the movie adaptation, director Andrzej Wajda made the communist party leader protagonist into a supporting role, and made a young guerilla planning an assassination—who had just a minor role in the original work—the protagonist in the movie. This protagonist is a freewheeling and unattached young man with weird-looking glasses. He falls in love with the girl at a bar—who is like a diamond in the ash—and they understand each other’s circumstances of their families being massacred by German soldiers; with this, he begins to transform—once he takes off his glasses—into a lonely handsome man resembling James Dean. I think the reason this movie is hard to understand is that the political situation at that time was complicated, and in order to pass censorship, the movie minimizes conversation and uses many metaphors.

There of course was severe censorship of movies by the Communist Party of Poland. Except for the protagonist in the original becoming a supporting role, the movie remains faithful to the original work that was approved by authorities, and the last scene with the young man dying in the landfill like worthless ash seems to warn, “Hahaha, that’s what happens when you rebel against the Communist Party.” However, it is said that those who were censoring felt something suspicious about this movie, and that they discussed with Moscow seriously about whether or not to approve this movie. In the end, since there wasn’t anything concrete that could be blamed, it passed censorship. However, because the movie received overwhelming praise in Western Europe when the producer put himself in danger by submitting it to the Venice Film Festival, the communist administration felt, “I don’t know what it is, but there must be anti-establishment thought inserted into this movie.” After this, director Wajda—who was already watched closely by the authorities—was completely blacklisted.

There of course was severe censorship of movies by the Communist Party of Poland. Except for the protagonist in the original becoming a supporting role, the movie remains faithful to the original work that was approved by authorities, and the last scene with the young man dying in the landfill like worthless ash seems to warn, “Hahaha, that’s what happens when you rebel against the Communist Party.” However, it is said that those who were censoring felt something suspicious about this movie, and that they discussed with Moscow seriously about whether or not to approve this movie. In the end, since there wasn’t anything concrete that could be blamed, it passed censorship. However, because the movie received overwhelming praise in Western Europe when the producer put himself in danger by submitting it to the Venice Film Festival, the communist administration felt, “I don’t know what it is, but there must be anti-establishment thought inserted into this movie.” After this, director Wajda—who was already watched closely by the authorities—was completely blacklisted.

The circumstances of Poland during World War II are depicted in director Wajda’s Katyń. Even with the change in the political system, his attitude did not waver at all over the 50 year period between these movies, and he persevered through his hard times in Poland without choosing to flee his country. It is no wonder he is respected.

In this movie, a guerilla, who is targeting the life of a Communist Party politician, is a member of an anti-Germany partisan group. It may be hard to understand why these people who oppose Germany are attempting to assassinate a communist—who aligns with the Soviet Union that chased away Germany—without understanding the situation of those days.

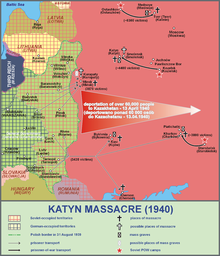

In August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union entered the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression treaty, and a secret stipulation within that treaty was that Germany and the Soviet Union would divide Poland. That following September, they started invading Poland, with the German and Slovakian armies from the west on September 1, and the Soviet Army from east on the 17th. The Polish government escaped to London and formed the “Polish government-in-exile,” which guided partisans in Poland. For the Polish government-in-exile, the Soviet Union was the abominable country that had, with Germany, invaded Poland; but when forced to choose between the Nazis and the Soviet Union, the Polish government had to choose the Soviet Union as an ally because Great Britain had already allied to the Soviet Union. However, there was the Katyn incident, and Poland did not trust the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union established a communist puppet government in Poland—separate from the Polish government-in-exile in London—that followed orders from the Soviet Union and opposed the partisans led by the government-in-exile that was supported by Great Britain. After all, World War II was a conflict between Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union, and because of Poland’s geographical location, the true nature of the conflict became clear in Poland. Under the orders of the Polish government-in-exile, the partisans in Poland rose up against Germany several times, and the largest of these was the Warsaw Uprising in June of 1944. This uprising was actually proposed by the Soviet Union, but the Soviet Army cut off support to the revolting army at a critical time. In the end, it became a battle between the German army and the Polish resistance Home Army. Hitler, concluding that the Soviet Union Red Army had no intention at all to rescue Warsaw, ordered for the suppression of the resistance Home Army and complete destruction of Warsaw. The Polish resistance Home Army had overwhelming support from the citizens of Warsaw, and they put up a good fight, but in the end, the army failed with the uprising. Many in the Home Army died, but those who survived escaped via underground water tunnels. Warsaw was destroyed as a punitive attack by the German army; after this, participants in the uprising were considered terrorists, and about 220,000 partisans and citizens were executed. After the uprising settled, the Soviet Red Army finally resumed their attack and occupied the ruins of Warsaw in January 1945. Afterwards, the Soviet Red Army arrested partisan leaders, and oppressed partisans wishing for Poland’s independence.

Ashes and Diamonds depicts four days, over which Commissar Szczuka moves to a Polish town for his new job as the occupying commander after Germany surrendered in 1945, and partisan Maciek, who has no relatives, receives orders and plans Szcuka’s assassination. For Britain, America, and France of the Allies, Germany’s surrender was the first step toward happy days, but for Poland, it was an ominous sign for their uncertain future.

After the failure of the Warsaw Uprising, the partisans supported by Great Britain finally recognized the Soviet Union as their true enemy, and made the Soviet Union the target of their attacks. The few surviving anticommunist partisans hid in the forest and resisted the Soviet Union, but since it became clear that the Soviet Union would be the ruler of Poland, resistance was futile. Director Wajda modeled Maciek after James Dean, who became an international star with Rebel Without a Cause, and he asked Zbigniew Cybulski who played Maciek to study James Dean. In fact, after the success of this movie, Zbigniew Cybulski came to be called the “Polish James Dean.” James Dean and Zbigniew Cybulski were the same generation, and James Dean died in a traffic accident at the age of 24, while Zbigniew Cybulski died in an accident when he was 39. Keiichiro Akagi—said to be the Japanese James Dean—also died young in a traffic accident when he was 21 years old.

After the failure of the Warsaw Uprising, the partisans supported by Great Britain finally recognized the Soviet Union as their true enemy, and made the Soviet Union the target of their attacks. The few surviving anticommunist partisans hid in the forest and resisted the Soviet Union, but since it became clear that the Soviet Union would be the ruler of Poland, resistance was futile. Director Wajda modeled Maciek after James Dean, who became an international star with Rebel Without a Cause, and he asked Zbigniew Cybulski who played Maciek to study James Dean. In fact, after the success of this movie, Zbigniew Cybulski came to be called the “Polish James Dean.” James Dean and Zbigniew Cybulski were the same generation, and James Dean died in a traffic accident at the age of 24, while Zbigniew Cybulski died in an accident when he was 39. Keiichiro Akagi—said to be the Japanese James Dean—also died young in a traffic accident when he was 21 years old.