Fantasia and the “Disney Acid Sequence”

Fantasia is an interesting film because it was created at a time when film was highly experimental and the sky seemed the limit on what new genres of art would be created by the technology of moving pictures. Fantasia imagines what the symphony of the future might look like: instead of going to the philharmonic, you might go to a movie that functioned as a concert that combined imagery with musical performance. Combining animation and song had long been a staple of early animation and film and still is, but it usually came in the form of short, humorous musical segments rather than a full-length, two-hour “concert.”

Fantasia consists of seven animated segments visualizing Classical, Romantic, and Modernist music, interspersed with stylized live-action sections introducing the conductor, the orchestra, and the various pieces of music. Each of the animated segments has its own style and mood, ranging from purely abstract (Toccata and Fugue) to concrete imagery without much story (Nutcracker Suite) to a coherent story (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice) but overall the art style from segment to segment is coherent enough that moving from one piece to the next isn’t too jarring. The result is a work of art and beauty that’s truly an experience to watch.

Fantasia didn’t turn a profit, but it got a second life when the psychedelic aesthetic came into vogue because, frankly, the visuals of the movie can be quite trippy, featuring dancing mushrooms and flowers, hippos and ostriches doing ballet, Dionysian orgies, and brightly-colored circles and lines moving across the screen in ways that, when combined with music, seem oddly… threatening at times? It seems that music plus the combination of drawn art and movement that animation consists in can become a quite trippy experience, especially as the art becomes more abstract/experimental or less photorealistic. This phenomenon is captured fairly well by the concept of the Disney Acid Sequence.

It’s important to note that sequences where the animation becomes detached from reality don’t necessarily indicate that the characters are under the influence of mind-altering drugs, that the animators are under the influence of mind-altering drugs, or that the viewer has to be under the influence of mind-altering drugs in order to appreciate them. In fact, I think the opposite is true in all cases:

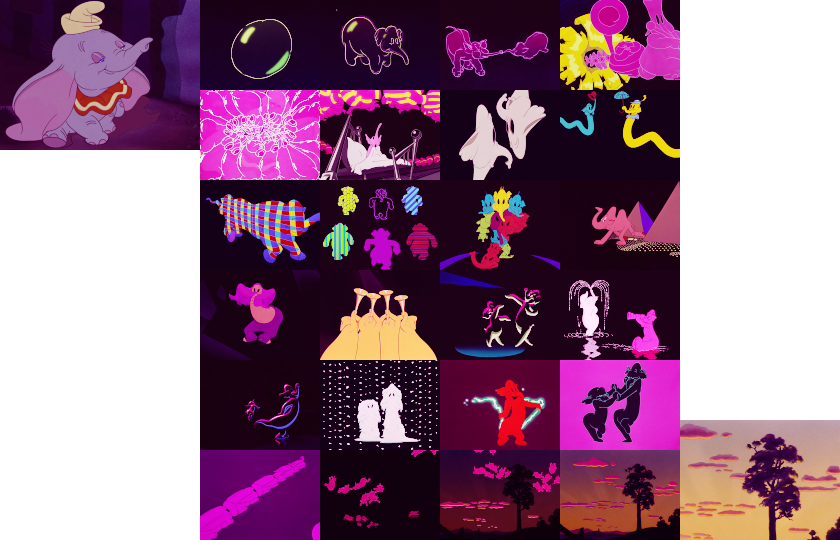

First, while it’s true that the art style suddenly getting weird can be an effective way to indicate an altered mental state visually — see: the drunk “Pink Elephant” hallucinations of Dumbo — they are just as often used in non-altered state scenarios such as daydreaming or to indicate someone is relating a tale/fantasy (where an art style change is used to indicate a story-within-a-story). So the narrative purpose of Disney Acid Sequences extend far beyond just the depiction of altered mental states and include things like nested storytelling.

The Pink Elephants sequence is an example where a change in art style is used to convey altered mental states and dreaming.

However, Disney Acid Sequences can be used to depict lucid mental states. For example, “You’re Welcome” from Moana uses stylized animation/art to convey a story-within-a-story. “Sing, Sweet Nightingale” departs from realistic art to convey Cinderella’s daydreaming.

Second, in terms of what’s happening on the animators’ side, it’s true that the end results of art style experimentations frequently look very trippy. However, the motivation for making them is much more mundane: it’s just normal artistic/creative experimentation. A Disney Acid Sequence may be a great excuse to do a loving pastiche of a particular art style, for example.

In addition to conveying daydreams, the “A Girl Worth Fighting For” segment from Mulan is an excuse to have the animation imitate Chinese ink wash and calligraphy, while the “Almost There” segment of Princess and the Frog pastiches the look of art deco advertising. Image credits: Calligraphy; painting by Shen Zhou. Art deco poster, Rolls-Royce ad

Finally, so-called Disney Acid Sequences are often the most fun and entertaining musical segments of a Disney movie in a way appreciable to everyone, not just the stoned, because of the amount of care, creativity, and art-style homage that may be put into them, and because stylized, non-photorealistic art styles are just… really cool to look at! This is not strictly a Disney Acid Sequence, but some of my favorite credit sequences are the credits for WALL-E and Ratatouille because of the stylized visuals and visual storytelling. (Try to name all the art styles featured in the WALL-E credits!)

Anyway, this is all to say that the whole of Fantasia is a Disney Acid Sequence, and that is what makes the film stupendous to watch (no drugs needed!).

Fantasia 2000

While originally Fantasia was intended to be a movie continually re-released with updated/shuffled segments, in fact it would not get an update until around 60 years later with Fantasia 2000. While this sequel to Fantasia certainly kept the bold, experimental spirit of the original, it falls short in terms of artistic achievement / the quality of final product. As a result, it is a bit of a disappointment to watch.

Core to both the creative energy and the disappointing results is the use of computer-generated (CG) animation. Experimenting with this (at the time) emerging technology and combining it with traditional animation was bold, putting the movie’s animation at the intersection of art and cutting-edge technology. However, CG animation at the time was still pretty crude and had not caught up to the visual standards of hand-drawn animation. Even now, even though CG animation has gotten much more fluid and visually impressive, the ability of CG animation to portray the non-photorealistic and/or abstract styles best exemplified by the “Disney Acid Sequence” is still limited when compared to hand-drawn animation, and often needs to be combined with hand-drawn animation in order to achieve the same level of quality.

In any case, while there was clearly effort and artistic vision put into Fantasia 2000, the technology wasn’t ready (and perhaps still is not ready) to rise to the level of the stunning visuals of the original. The idea was sound, however, and I hope that Disney plans to continue to update Fantasia and its type of musical/visual storytelling as the technology gets yet more mature.

(There are of course many more examples of beautiful stylized animation both inside and outside of Disney. Just a short list of examples I’ve encountered: Destino’s Dali-inspired art, the storybook art of The Tale of Princess Kaguya, a film about Vincent van Gogh done in the style of his paintings, and the look of Into the Spider-verse inspired by comic books and pop art.)

Unfortunately, the dream of Fantasia becoming the future of the symphony didn’t really pan out — but if you go to the symphony, they will sometimes make use of picture screens, so that at least has come true.