This movie depicts the emotional bond between an aging Czech musician and a Russian boy living in then-Czechoslovakia in 1988. The time depicted is the turbulent period leading up to the Velvet Revolution, which was the relatively peaceful overthrow of the Communist Party government and one of the events marking the end of the Cold War.

This movie depicts the emotional bond between an aging Czech musician and a Russian boy living in then-Czechoslovakia in 1988. The time depicted is the turbulent period leading up to the Velvet Revolution, which was the relatively peaceful overthrow of the Communist Party government and one of the events marking the end of the Cold War.

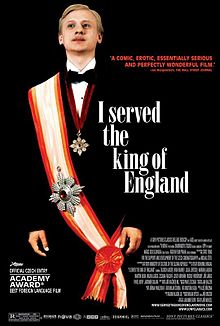

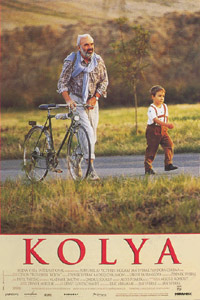

Once a top cellist, Louka is now poor and makes a living with various part-time jobs. In exchange for money, he reluctantly has a sham marriage with a Russian woman in order for her to get a Czech passport, but this woman leaves behind her five-year-old son, Kolya, with his aunt and flees to West Germany. However, the aunt suddenly dies, and Louka is left to care for Kolya. At first, they feel awkward with each other, but gradually affection grows between the two. However, since Louka’s older brother also fled to the West, the secret police suspect Louka of helping the Russian woman flee the country with a fake marriage, and they start an investigation; also, a female social worker appears and is going to send Kolya to an orphanage in Russia… The story continues on, and ends with Czechoslovakia succeeding with the Velvet Revolution and overthrowing the rule of the Soviet Union.

Since the little boy who plays Kolya is too cute, and the story is filled with light humor and wit, one would think this movie is a heart-warming story of love between the little boy and the cellist, but I think this movie wants to depict the resentment of Czechs towards the rule of the Soviet Union, the day-to-day life of the people living under Soviet rule, and the emotional responses of people during turbulent times. The impression I get is that sweet Kolya is used to make the movie charming, but Kolya is just a cute child to an adult, and the depiction of the boy’s emotions is shallow. Also, Louka is depicted as an irresponsible man who chases after women. Is he just pretending to be an irresponsible womanizer in order to avoid attention after losing his former top social status, or is this his true personality? I can’t tell because Louka’s depiction is not deep enough. Perhaps the reason for depicting Louka this way is that the movie wants to draw a dramatic contrast between him at first being irresponsible and at the end being loving. However, the love that develops between the sweet-looking child and the cartoon-like adult is not very persuading. If this is a story of love, I must say it is a story made without the understanding of love.

Since the little boy who plays Kolya is too cute, and the story is filled with light humor and wit, one would think this movie is a heart-warming story of love between the little boy and the cellist, but I think this movie wants to depict the resentment of Czechs towards the rule of the Soviet Union, the day-to-day life of the people living under Soviet rule, and the emotional responses of people during turbulent times. The impression I get is that sweet Kolya is used to make the movie charming, but Kolya is just a cute child to an adult, and the depiction of the boy’s emotions is shallow. Also, Louka is depicted as an irresponsible man who chases after women. Is he just pretending to be an irresponsible womanizer in order to avoid attention after losing his former top social status, or is this his true personality? I can’t tell because Louka’s depiction is not deep enough. Perhaps the reason for depicting Louka this way is that the movie wants to draw a dramatic contrast between him at first being irresponsible and at the end being loving. However, the love that develops between the sweet-looking child and the cartoon-like adult is not very persuading. If this is a story of love, I must say it is a story made without the understanding of love.

Information provided by the radio and newspaper about the times is inserted throughout this movie, so the audience is able to understand what is happening in the outside world. Conversations between the people are frequently about how annoying Soviet Union soldiers are. In the end, this movie made after the victory of the Velvet Revolution seems to have the intention of documenting, “what life was like for people under the tyrannical rule of the Soviet Union,” and that, “Czechs hated the Nazis. But the Soviet Union that came afterwards was as bad.” First Secretary Alexander Dubček played a central role in the “Prague Spring” reformation movement in 1968, but the Warsaw Treaty Organization led by the Soviet Union later crushed it with a military intervention; Czechoslovakia became a secret police nation like East Germany, and people lived holding their breath, in fear of being informed on.

However, things have certainly changed. Hungary at last decided to open the national border with Austria in 1989. Since it was feasible for people of East Germany to make their way to Hungary, many East Germans started trying to enter Hungary; from there, they could cross the national border to Austria, then from there, move to West Germany. Also, just like Kolya’s mother in this movie, people from Russia moved to Czech territories—where entry was allowed—and planned to use a Czech passport to flee further to West Germany. Even if East Germany citizens didn’t have a Hungarian passport, countless East Germans went to Hungary in hopes of somehow crossing the national border to Austria.

In August of 1989, the Hungarian Democratic Forum held the Pan-European Picnic in Sopron, the Hungarian town nearest to Austria. Rumors saying that those who participated in this meeting could cross over the national border spread, and a great number of East Germany citizens gathered in this town; one after another, they started to cross the national border, but Hungarian authorities didn’t stop them. This news spread within East Germany, and even more citizens of East Germany gathered at the Hungary and Czechoslovakia borders in order to cross over to Austria and West Germany, respectively. Stimulated by this news, citizens in East Germany demanded more and more for freedom, and the Berlin Wall at last came down on November 10, 1989. On November 17, the Velvet Revolution broke out in Czechoslovakia, and the Communist Party administration collapsed. The Soviet Union did not intervene anymore. The humiliation of the Prague Spring was not repeated.

Zdeněk Svěrák, who played Louka in this movie, also wrote the script, while his son Jan Svěrák directed the movie. Jan Svěrák was only 30 years old when he picked up the megaphone for this movie, and he was a 23-year-old student when the Velvet Revolution happened. This movie seems to be loaded with Zdeněk’s desire to convey to the young generation, including his son, what life was like under the Soviet Union system, and the hope he has as a father for his son’s future. Zdeněk Svěrák was 32 years old when he experienced the Prague Spring.