Once, this movie was celebrated as a masterpiece and won many awards in the West; but this movie has already slipped into obscurity, and it has become difficult to obtain it on DVD. It seems that movie director Sergei Parajanov—once regarded as an internationally renowned maestro—has also slipped into obscurity. In this movie, he used techniques that were novel for the time and astonished viewers, similar to his close friend director Andrei Tarkovsky (Ivan’s Childhood). However, because the next generation of directors in many countries imitated and often used these new techniques, it is very difficult today to see and appreciate the newness; also, the reputation of this movie within the Soviet Union was bad due to Sergei Parajanov being one of the victims who were buried under the political oppression of the Soviet Union administration.

Once, this movie was celebrated as a masterpiece and won many awards in the West; but this movie has already slipped into obscurity, and it has become difficult to obtain it on DVD. It seems that movie director Sergei Parajanov—once regarded as an internationally renowned maestro—has also slipped into obscurity. In this movie, he used techniques that were novel for the time and astonished viewers, similar to his close friend director Andrei Tarkovsky (Ivan’s Childhood). However, because the next generation of directors in many countries imitated and often used these new techniques, it is very difficult today to see and appreciate the newness; also, the reputation of this movie within the Soviet Union was bad due to Sergei Parajanov being one of the victims who were buried under the political oppression of the Soviet Union administration.

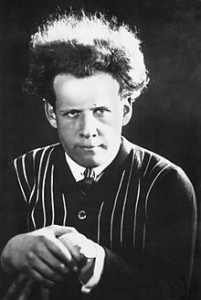

Sergei Parajanov was born in 1924 in Georgia (in Japan, people tend to call it Grúziya in the Russian style, but the Georgian government demanded that it be internationally called Georgia in the English style), and studied cinematography at the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography in Moscow. He is ethnically Armenian.

Georgia is on the south side of the Caucasus Mountains, which connects the Black and Caspian Seas, and it has Russia to the north, Turkey to the south, and Armenia and Azerbaijan as neighbors. Since ancient times, this area was an important traffic route used by many ethnicities, and it was the focus of Russia’s plans for southern expansion; under the 1783 Treaty of Georgievsk, the eastern part of Georgia became a protectorate of Russia. Georgia, as a pious Greek Orthodox Church nation, needed Russia’s support in order to prevent Islam nations—such as Turkey and Persia, who feared Russia moving south—from invading Georgia. In other words, Georgia decided that it was necessary to rely on Russia in order to protect itself from the threat of Muslim Persia and Turkey—the Islamic power that coexisted in the Caucasus area. In 1801, Georgia—caught up in internal turmoil—was annexed into Russia. Later, in 1832, aristocrats in Georgia developed a plan to overturn Russian control, but it was soon suppressed by Russia. When the Russian Revolution broke out, Georgia declared independence from Russia, but the Soviet Union suppressed this, and Georgia became a part of the Soviet Union. Partly because Stalin was from Georgia, Georgia—until it declared its independence in 1991—was relatively obedient to the central government of the Soviet Union, and was not considered to be a problem child by the Soviet Union.

Sergei Parajanov married a Ukrainian woman and continued artistic activities in Ukraine, but gradually his avant-garde artistic style became considered to be anti-establishment, and he began to be oppressed by the Soviet Union socialist administration. In the Soviet Union, only movies that used a socialist and realistic style and praised socialism were allowed; avant-garde and surrealist movies, like those of Sergei Parajanov, were considered degenerate and dangerous movies that were hiding something. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors was showered with high praises all over the world, but it was unpopular in the Soviet Union. Sergei Parjanov was increasingly oppressed by government authorities, and in 1974, he was imprisoned for the crime of homosexuality. Regarding his imprisonment, European directors including Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini, Luchino Visconti, François Truffaut, and Jean-Luc Goddard organized a protest campaign; Sergei Parajanov was released three years later, but even after that, he received relentless oppression from Soviet Union authorities, so it became impossible to make a movie. Due to this cruel situation, he later immigrated to Armenia.

Ukrainian Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky wrote the original Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky was born in 1864 in Ukraine—which was under Russian control at that time—and was part of a literature movement that focused on traditional Ukrainian culture, which was under severe oppression by the Russian Empire in those days. West Ukraine was under the control of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time; since more Ukrainian cultural activity was allowed there than in Russia-controlled areas, he published his books in West Ukraine. Director Sergei Parajanov is not Ukrainian, but perhaps he felt a sort of commonness with Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky who was involved in the Ukrainian literature revival movement.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is the Ukrainian version of the story of Romeo and Juliet, where a young boy from a mountain tribe in West Ukraine falls in love with the daughter of the rival family that killed his own parents. The movie depicts in vivid color the life of people who are Greek Orthodox—a religion that was strictly prohibited by the Soviet Union in those days; this movie suggests that religion was the standard for living, and that people lived in fear of supernatural phenomenon such as ghosts. The depiction of religion alone appears to be enough to rub socialist authorities—who banned all religions (but adhered religiously to Marxism)—the wrong way. Moreover, this movie goes beyond any possible acceptable range by depicting Ukrainians—who were hated by Soviet authorities for having been a threat to Russia, such as with the revolt of the Cossack soldiers, and attempting independence when the Soviet Union was established.

The Duchy of Kiev existed in the area of current Ukraine, but it was destroyed in the 13th century by the Mongolian Empire. After the Mongolian Empire, this area belonged to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the north and the Kingdom of Poland to the west, but gradually a semi-military community called Cossacks developed, and they began to resist control by foreign powers. However, due to the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667, Ukraine was divided; West Ukraine was placed under the control of Poland—later the Austro-Hungarian Empire—and East Ukraine was placed under the control of Russia. Taking advantage of the collapse of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires in World War I, Ukrainians living in West Ukraine declared their independence as the West Ukrainian People’s Republic; Poland opposed this, and thus the Polish-Ukrainian War began. The Polish side was supported by France, Britain, Romania, and Hungary. Against this, West Ukraine appealed for support from the Ukrainian People’s Republic to the east. However, the Ukrainian People’s Republic government could not dispatch reinforcements since they were fighting against the Soviet Red Army; in the end, West Ukraine was occupied by Poland, and the West Ukrainian People’s Republic collapsed.

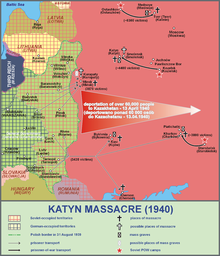

The Ukrainian People’s Republic to the east was put under Soviet Union control; the Soviet Union led by Lenin and Stalin adopted hostile policies toward Ukraine. One reason was that Ukraine was a fertile agricultural nation, so the socialist policy that was based on factory workers was not applicable to the economic system of Ukraine. Because the socialist policies that did not fit Ukraine’s reality were enforced, the agriculture of Ukraine suffered devastating damage, and a great many people died of famine. Stalin’s Great Purge also started from Ukraine.

In World War II, Ukraine—due to its close proximity to Germany—suffered enormous damage, and among the Soviet Union, Ukraine was the greatest victim of World War II. It is said that 1 in 5 Ukrainians died in the war. People’s stance during the war was also complicated in this area; there were some people who supported the Soviet Union side, while other people supported the German side. Also, there were people who joined the anti-Soviet, anti-German Ukrainian Insurgent Army, and fought for Ukraine’s independence. Ukraine, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, became a new independent nation in 1991, but Ukraine and Russia are still tied together in many ways. The government is also torn between the anti-Russia faction and the pro-Russia faction.