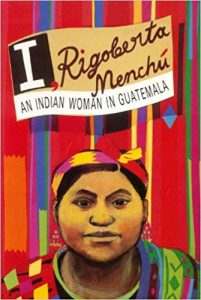

Rigoberta Menchú is a revolutionary Mayan activist from Guatemala who grew up as the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996) was escalating across the country. In 1982, a Venezuelan anthropologist interviewed the then-23-year-old Rigoberta and compiled her words into the book I, Rigoberta Menchú. Rigoberta speaks with a matter-of-factness about the many horrible and violent events she witnessed, saying her story is the story of all poor and indigenous Guatemalans. With this book, an international spotlight was put on the violent state of affairs in Guatemala. Rigoberta was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992 for her activism.

Rigoberta Menchú is a revolutionary Mayan activist from Guatemala who grew up as the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996) was escalating across the country. In 1982, a Venezuelan anthropologist interviewed the then-23-year-old Rigoberta and compiled her words into the book I, Rigoberta Menchú. Rigoberta speaks with a matter-of-factness about the many horrible and violent events she witnessed, saying her story is the story of all poor and indigenous Guatemalans. With this book, an international spotlight was put on the violent state of affairs in Guatemala. Rigoberta was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992 for her activism.

Rigoberta attributes her revolutionary roots and the resiliency of indigenous communities to several factors.

One, the extreme suffering and poverty experienced by most indigenous communities. Indigenous people were often terribly discriminated against and exploited by lighter-skinned Guatemalans of European descent. In her testimony, Rigoberta shares many moments where she felt she and those around her were treated worse than animals, being described as “dirty Indians” who were poor because of their laziness and ignorance.

Rigoberta explains how people living through such hard times do not get to have a childhood—always working, not having the chance to go to school, and never eating enough. By the age of 8, she was working in the fields alongside her mother, earning money to help support her family. Before that, she was helping with childcare, fetching water, and caring for their animals. Rigoberta said she was scared to grow up after watching crying mothers bury their sick and starving children. Rigoberta rightly acknowledges that revolutionaries are not born out of something good, but rather out of wretchedness and hardship.Two, there is huge cultural importance of community and the land. She recalls her elders telling her, “Land belongs to everyone, not one person,” and that, “No one should accumulate things the rest of the community does not have.” In her culture, at the age of ten, there is a ceremony of adulthood where one makes a promise to their elders to contribute to their community. She also speaks of how her people are rooted in corn and the land. Because of this, when their shared land was threatened, communities were prepared to fight to defend their land.

Three, Rigoberta’s father, Vicente Menchú, was a big influence on her. Vicente was a leader in their community, and he worked with unions and the CUC (Comite de Unidad Campesina, or the Peasant Unity Committee) to unite peasants through their shared oppression by the wealthy. Rigoberta, as her father’s favorite, accompanied him on many of his visits to the city. She recalls her father often lamenting the unjust removal of the democratically-elected Árbenz from power back in 1954.

Because of his organizing activity with these groups and eventually the guerillas in the mountains, Vicente was targeted and arrested by the government. Illiteracy in Spanish (due to it not being their native language as well as not having the opportunity to study in school) meant indigenous people were particularly at the mercy of the system. Rigoberta aptly notes that, “Prison is a punishment for the poor,” when she recalls how her family was forced to pay money to lawyers, translators, and bureaucrats for a year and a half before her father was set free. Her father was later kidnapped and tortured by landowners and again arrested in 1977 for being a communist and enemy of state.

In 1980, Vicente joined others from the CUC in the occupation of the Spanish Embassy in an attempt to raise awareness internationally of the state of affairs in Guatemala. Police were sent in and set the embassy on fire, resulting in the death of Vicente and all 36 other activists and diplomats present.

Violence plagued her family. Rigoberta’s mother was also kidnapped and raped before being killed in 1980. The military captured Rigoberta’s little brother and other guerillas, brutally and publicly torturing them for being communists and “terrorists” from Cuba or Nicaragua. The military told all the surrounding villages that they had to watch or else be considered accomplices of the subversive actions of the guerillas. Furthermore, the justification was that, “Indians are ignorant,” so they are susceptible to the beguiling words of communism. Many soldiers likely did not know much about communism either, just simply that communists were the enemy and were hiding in the mountains.

Rigoberta’s little sister also joined the guerillas when she was 8. Rigoberta said she went many years without seeing her until they were reunited in Mexico, both among the tens of thousands of Mayans from Guatemala who were forced to flee to Mexico during the civil war.

—

Rigoberta began her organizing in the fields of sugar cane, coffee, and cotton. Most peasants spent part of each year working on farms owned by rich landowners. It was very exhausting work; peasants were paid based on how much they harvested, but were penalized and received deducted pay for everything from damaging a plant to any food or drinks consumed. Workers had to live in austere and inhumane conditions, were often credited for less weight harvested when being paid, and sometimes were even kicked out without pay. Rigoberta recalls once forsaking payment to clean up the body of a woman who was violently killed with a machete by the son of the landowner.

Despite all of the peasants working on these farms being from indigenous communities, there were always barriers because families from different areas spoke different languages and had cultural differences. Therefore, despite their shared pain under difficult work conditions, the workers were still isolated and divided. With 22 languages spoken among various indigenous groups, Rigoberta actually chose to harness Spanish, the language of their shared oppressors, to unify and organize indigenous peasants. Rigoberta had a bit of privilege to have the opportunity to learn some Spanish through her time at a Catholic boarding school and during the time she spent working as a maid for a rich family in the city. There was a fear among indigenous communities that having their children learn Spanish at the “white man’s schools” would change them and cause them to abandon their people. However, Rigoberta understood the power of language as a critical tool and learned to speak and read Spanish in order to navigate the system of the oppressors and communicate with many different people. Rigoberta was able to build solidarity among different indigenous communities because, despite their differences, she saw how they were all connected to the land and shared the same oppression.At their prime in 1980, the CUC organized a strike among farmworkers that garnered the win of more than doubling the minimum wage. This strike lasted for 15 days and included over 70 thousand workers across sugarcane and cotton farms.

—

Beyond the farm, Rigoberta also talks of organizing indigenous communities on their land. When Árbenz’s land reform was reversed, the government ordered to have land taken away from indigenous communities and given to rich landowners; government soldiers began to invade villages to kick people off of their land. Some people were given the option of either leaving their land or staying to work as an indentured servant. Predatory lawyers and government officials would offer to help peasants keep their land, charging them as they encouraged them to keep cultivating the land; meanwhile, the peasants had already unknowingly signed their rights to their land away on a document that they could not read. (This abuse of the illiterate was seen during elections as well, when all the workers on a farm were forced by the landowner to check a certain box on a paper, unknowingly casting a vote for President on a ballot that they couldn’t read. This was one way the dictatorships dealt with Arévalo’s expansion to suffrage.)

Rigoberta’s community was initially allowed to keep their land, but their shared land was divided by the government into small separate plots, which were not enough to live on, and they were told one could be arrested if they even cut down a tree not on their own land. This was an intentional effort to weaken the community and destroy collective structures. Her village refused these changes and began to organize to be able to fight back, developing traps and security against the landowners and soldiers that would come to terrorize their village and take their food. With the strong sense of community and connection to the land, the whole village was ready to all die together.

When Rigoberta felt assured that her village had organized sufficient defenses, she went to the communities of other women she had met while working on the farms to teach them these same strategies to protect their land.

—

Rigoberta talks a lot of “bad ladinos.” Ladino is the word for people of mixed European and indigenous descent, but is understood as those who have turned away from their indigenous roots, using whatever power they have gained to abuse their own people. Many of the farms that peasants had to work on were owned by ladinos; Rigoberta’s image of the ladino landowner is, “very fat, well dressed and even had a watch.” She says the government is made of ladinos and for ladinos. Some ladinos acted as hired ears for the military to provide information of the activity of communities and guerillas in the mountains to the government.

As seen throughout history and across the world, deep and deliberately sown divisions along racial lines have weakened efforts by the poor and working class to fight back against the rich. Even poor ladinos would say, “I’m poor, but at least I’m not Indian.” As Rigoberta began talking to indigenous and ladino peasants alike, she understood the shared struggle of being poor and exploitation by the rich. Activists and groups such as the CUC had to intentionally work to bring both poor Mayans and ladinos into the movement.

—

Throughout her testimony, Rigoberta discusses some of the traditions of her people, though remains wary of revealing too much in fear of the destruction or appropriation of the customs and culture of her people. Given the long and violent history of colonialism, there is a very real fear of the loss of culture; indigenous communities must find the balance between the conservative desire to preserve traditions and the need to adapt to changing times. The extreme and violent times of the civil war meant having to break from cultural traditions, as the community no longer had time for ceremonies.

Rigoberta talks of gendered traditions and how men and women were typically kept separate. She says women cooked, managed money, cleaned clothes, quilted, encouraged men, supported children, and have a unique connection to the earth as mothers. As with their ceremonies, gender divisions were eroded during the extreme times of the war, as everyone had to unite and be prepared to fight back in any way. Women and children protested in solidarity with the men, fully aware that the army was vicious enough to kill them all. Rigoberta recalls her mother saying to her, “I don’t want to make you stop feeling a woman but your participation in the struggle must be equal to that of your brothers.”

Rigoberta talks of gendered traditions and how men and women were typically kept separate. She says women cooked, managed money, cleaned clothes, quilted, encouraged men, supported children, and have a unique connection to the earth as mothers. As with their ceremonies, gender divisions were eroded during the extreme times of the war, as everyone had to unite and be prepared to fight back in any way. Women and children protested in solidarity with the men, fully aware that the army was vicious enough to kill them all. Rigoberta recalls her mother saying to her, “I don’t want to make you stop feeling a woman but your participation in the struggle must be equal to that of your brothers.”

Rigoberta discusses how she debated the idea of getting married and having children. As a revolutionary, she was fighting for a better future for the next generation, but she knew the nature of the revolutionary work meant she could die at any time, leaving behind children or a widower. She also had the fear that a concern for personal happiness would selfishly pull her energy away from the needs of her greater community.

Rigoberta mostly praises her traditions, but does mention how she faced some machismo and sexism from other revolutionaries (including other women) who believed women could not be a fundamental part of the revolution. Rigoberta insisted that women fight alongside men because men need to help deal with the additional realities of rape and violence that women faced. She also believed strongly that any change without women would not be a victory.

Throughout Latin America, Catholicism had a strong presence and was incorporated into the traditions of most villages. Rigoberta recalls praying together in Latin or Spanish, even though they did not understand the words. She felt that Christianity had not replaced their beliefs, but rather was another form of expression. Rigoberta attended some Catholic school and was a catechist. In her testimony, she references Judith as a woman who fought for her people, David as the shepherd boy who wished to live off the land, and Christ as a humble man who was persecuted. She relates the way that Christ lives on through his apostles whenever they tell stories of him to how her elders live on in their children.Rigoberta was very religious, asserting that as a Christian, she refused to accept the injustices and violence committed against her humble people. However, she also acutely points out the hypocrisy of a supposedly Christian government carrying out the massacre of people. She says there are two kinds of Catholicism: one for the rich and one of the poor. She also says she fears that Catholicism and the promise of the land for peasants in heaven taught her people a passiveness and acceptance of violence and injustice that made them vulnerable to exploitation.

—

Rigoberta rebelled as an indigenous Mayan, a woman, a peasant, and a Christian. All of these parts of her shaped her revolutionary politics and desire to build intersectional solidarity. In 1981, Rigoberta was exiled and convinced to seek refuge in Mexico. She states how defeated she felt when she was forced her to abandon her country while the fight was still continuing.

After Rigoberta was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, there was controversy due to some historical inaccuracies of her internationally-renowned story. One professor released a book that picked apart several details, primarily the omission of her access to education at a Catholic boarding school when she was young and the fact that she had not personally witnessed her brother’s torture and death that she described in detail. He also raised concerns about people using Rigoberta’s story to glorify leftist resistance and downplaying some of the more violent actions of the guerilla forces such as the use of bombs. There was some discussion about rescinding her Nobel Peace Prize for the inaccuracies, but it appears that the overall consensus today is that her testimony—told as shared experience in a style common among indigenous communities—is the communal story of many indigenous people of Guatemala who lived through the Civil War. (Rigoberta states as much when she says her story is the story of all poor indigenous Guatemalans.) Many agree that this focus on specific inaccuracies does far-reaching damage to her credibility, perpetuates the long history of silencing indigenous voices, and problematically equates the violence of the guerilla forces with that of the military regime. Though certainly flawed and at times violent, the guerilla resistance did not commit the multitude of human rights violations that the U.S.-backed government and paramilitary in Guatemala did throughout the Civil War.

Rigoberta is still alive and now is 60 years old. She got married in 1995 and has one son. She continues to fight for women and indigenous rights as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. She co-founded the Nobel Women’s Initiative, which strives for “a democratic world free of physical, economic, cultural, political, religious, sexual, and environmental violence” as it affects women and all of humanity, and is a part of the PeaceJam Foundation with other Nobel Peace Laureates such as the Dalai Lama XIV, which wishes to inspire young people to work towards peace. Rigoberta has also gone on to write her own books, advocates for affordable medications and health care for Guatemalans, and is working to raise awareness of climate change.

Rigoberta is still alive and now is 60 years old. She got married in 1995 and has one son. She continues to fight for women and indigenous rights as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. She co-founded the Nobel Women’s Initiative, which strives for “a democratic world free of physical, economic, cultural, political, religious, sexual, and environmental violence” as it affects women and all of humanity, and is a part of the PeaceJam Foundation with other Nobel Peace Laureates such as the Dalai Lama XIV, which wishes to inspire young people to work towards peace. Rigoberta has also gone on to write her own books, advocates for affordable medications and health care for Guatemalans, and is working to raise awareness of climate change.