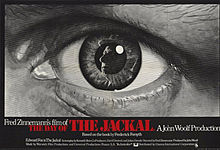

This is an extremely entertaining movie. If you were to classify this movie, it would be similar to the 007 James Bond series, the Jason Bourne trilogy, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, but it is way more enjoyable. Even though the current movie industry jam-packs movies with computer graphics, showy action, and explosion scenes, I feel like this movie hasn’t been surpassed in 40 years. The Day of the Jackal is on the list of “Akira Kurosawa’s Top 100 Films.” This movie is such a perfect movie that I believe Kurosawa would have wanted to make a movie like it. Of course, I think Kurosawa had the skills to make this level of movie, but unfortunately he was not able to find as excellent raw material as the original novel written by Frederick Forsyth. This movie’s director, Fred Zinnemann, was nominated many times for an Academy Award—including The Search, High Noon, From Here to Eternity, The Nun’s Story, A Man for All Seasons, and Julia—and won 4 Academy Awards in his lifetime.

This is an extremely entertaining movie. If you were to classify this movie, it would be similar to the 007 James Bond series, the Jason Bourne trilogy, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, but it is way more enjoyable. Even though the current movie industry jam-packs movies with computer graphics, showy action, and explosion scenes, I feel like this movie hasn’t been surpassed in 40 years. The Day of the Jackal is on the list of “Akira Kurosawa’s Top 100 Films.” This movie is such a perfect movie that I believe Kurosawa would have wanted to make a movie like it. Of course, I think Kurosawa had the skills to make this level of movie, but unfortunately he was not able to find as excellent raw material as the original novel written by Frederick Forsyth. This movie’s director, Fred Zinnemann, was nominated many times for an Academy Award—including The Search, High Noon, From Here to Eternity, The Nun’s Story, A Man for All Seasons, and Julia—and won 4 Academy Awards in his lifetime.

In this movie, “Jackal” is the codename for the assassin who is planning to assassinate France’s president de Gaulle. Of course, viewers that know history know that such a thing didn’t really happen. However, viewers sit at the edge of their seats until the very end, and they are completely drawn into the movie. It was reported that real, famous professional assassins read and loved the original work that this movie was based off of, and actually used it as a reference. This movie is a first-rate depiction of the international affairs France was involved in during the 1960s. Also, the attempted assassination of President de Gaulle, depicted in the first half of this movie, is a historical fact. Historical fact and fiction are skillfully combined in this movie, and this movie has magical persuasive power. At first, since it depicts Jackal’s viewpoint, the audience knows and understands what Jackal is doing, and they are captivated by Jackal’s cool charm. However, in the second half, the point of view shifts to that of the detective chasing Jackal, and we don’t know where Jackal is hiding or what he is thinking, so the amount of suspense in the movie increases. It is extremely well done. I can’t praise this movie enough.

In World War II, northern France was occupied by Germany, while Vichy France to the south was considered to be Germany’s puppet government. In spite of this, France is classified as a victorious nation, not a defeated country, in World War II; the reason is that French general Charles de Gaulle—who took refuge in Great Britain—led the Free French Forces, which joined the Allies and fought as an anti-Germany and anti-Vichy force. However, France, exhausted by World War II, nearly lost its status as one of the major powers in the world, and the colonial system from before the war became difficult to maintain. When the situation in Algeria became critical in 1954, France withdrew from Vietnam and turned their focus toward Algeria.

In Algeria, French colonization had been increasing since the 19th century, and colonists in Algeria were called Pied-Noirs. In World War II, Algeria supported Vichy France, but in 1942, Operation Torch was initiated by the Allies, and the U.S. and British armies invaded Algeria; when they landed, the Algerian admiral joined de Gaulle’s Free French Forces that supported the Allies and the headquarters of the Free French Forces was put in Algiers until the liberation of Paris. In this way, Algeria became a very important piece of land for France. Many native Algerians burned with patriotism, and participated in the French army as a French volunteer soldier.

After World War II, Algeria sought its independence, and the Algerian War began in 1954; this war became a very muddy situation, and it split French public opinion in half. The descendants of the Pied-Noir French settlers opposed Algerian independence, and right-wingers—who wanted to maintain their French glory—voiced their support for the colonists. Also, in those days, the French had deep-rooted fear and animosity regarding the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) that was responsible for extreme acts of violence. However, as a result of frequent wars, war weariness was also strong among public opinion, and so some believed that granting Algeria their independence was in the best interest of France. Even between native Algerians, there was a severe antagonism between a pro-French faction and an independence faction. During this political instability, the Fourth Republic—which had been established after World War II—was overturned, and the Fifth Republic was established upon Charles de Gaulle’s assumption as president.

Charles de Gaulle was the person who symbolized strong and glorious France, so the colonists and the soldiers in Algeria hoped de Gaulle would give them support, but on the contrary, de Gaulle announced his support for Algerian self-determination. The majority supported this in the national referendum of 1961, and in 1962, the war ended. Among the massive chaos, military personnel there and colonists fled to France, but many pro-France Arabs who were not able to escape were killed. The power that opposed Algerian independence formed the Organization of the Secret Army (OAS) during the war, and committed acts of terrorism one after another in Algeria; they also performed terrorist acts against de Gaulle to overthrow the government in France. Officer Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry failed with his attempt to assassinate de Gaulle, and he was executed by firing squad; this is where the movie begins. After the assassination attempt, the de Gaulle administration chased down the OAS with every hand they had.

However, a new enemy was born for de Gaulle: a leftist movement led by students and laborers. In order to suppress the May 1968 events caused by this movement, he needed military power, and so de Gaulle granted amnesties to major OAS members who had been arrested/fled.

As I mentioned before, this movie is absolutely incredible and praiseworthy, but this movie has one flaw. This movie is an American movie; all of the characters—including the French ones—speak English. This movie moves around many European countries—Austria, Switzerland, Britain, Italy, France, Denmark, etc.—and since all the major characters speak English, it’s hard to tell what country we are in currently. I still don’t understand why American movies insist on using only English.