The Nuremberg Trials are a historical fact. However, this movie is a work of fiction that instead captures the feel of history by being based on actual facts; it can be said that it aims to depict the world after World War II from the point of view of the American conscience during the Cold War.

The Nuremberg Trials are a historical fact. However, this movie is a work of fiction that instead captures the feel of history by being based on actual facts; it can be said that it aims to depict the world after World War II from the point of view of the American conscience during the Cold War.

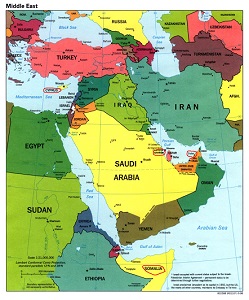

After the end of World War II, military leaders from the victorious nations—U.S.A., Britain, France, and Russia—gathered in Nuremberg in order to judge German war criminals. In the first half of the trial that began in 1945, the highest German leaders that led the war were one-sidedly judged and sentenced severely, but this movie is set in 1948, when the global situation surrounding the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials had subtly changed. For the U.S., Britain, and France, the threat was no longer Germany, but rather the Soviet Union. The Soviet Army occupied the eastern part of Germany, and it seemed to have its eyes set on occupying all of Germany. The U.S., Britain, and France concluded that, if the Soviet Union took control of Germany, all of Europe would bit by bit be taken over by communism; therefore, the interest of the U.S., Britain, and France became to protect Germany from the Soviet Union and the spread of communism, rather than punishing Germans.

The movie begins with a U.S. district court judge, Haywood (Spencer Tracy), being appointed as the Chief Trial Judge for one of the cases in the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials, and thus him going to Nuremberg. The reason he is appointed is that this case is judging some of Germany’s highest-class lawyers; in particular, since one of the defendants is Dr. Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster)—who is internationally known and acted as the Minister of Justice at the time of the Nazi’s defeat—no one wants to be the judge of the trial, so the duty is imposed on nameless, honest Judge Haywood.

The movie begins with a U.S. district court judge, Haywood (Spencer Tracy), being appointed as the Chief Trial Judge for one of the cases in the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials, and thus him going to Nuremberg. The reason he is appointed is that this case is judging some of Germany’s highest-class lawyers; in particular, since one of the defendants is Dr. Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster)—who is internationally known and acted as the Minister of Justice at the time of the Nazi’s defeat—no one wants to be the judge of the trial, so the duty is imposed on nameless, honest Judge Haywood.

Judge Haywood and the American officers staying in Nuremberg are impressed by the German traditions and the depth of the culture. After the war, even though they are poor, people drink delicious beer, enjoy a beautiful chorus in a bar, and appreciate piano and opera musical performances. People are kind, as if everyone is trying to prove that, “Germans are not beasts, like the world believes.” The officers, who came here as part of a victorious nation, make fun of themselves with, “We are like those Boy Scouts that walk around a beautiful palace with muddy shoes.” If there hadn’t been a war, I think Americans would have aspired for German culture. Judge Haywood, who is among these Americans, and prosecutor Colonel Lawson (Richard Widmark) are implicitly pressured from higher powers to quickly complete the trial, and to not give a severe sentence in order to win over Germany’s support.

Judge Haywood and the American officers staying in Nuremberg are impressed by the German traditions and the depth of the culture. After the war, even though they are poor, people drink delicious beer, enjoy a beautiful chorus in a bar, and appreciate piano and opera musical performances. People are kind, as if everyone is trying to prove that, “Germans are not beasts, like the world believes.” The officers, who came here as part of a victorious nation, make fun of themselves with, “We are like those Boy Scouts that walk around a beautiful palace with muddy shoes.” If there hadn’t been a war, I think Americans would have aspired for German culture. Judge Haywood, who is among these Americans, and prosecutor Colonel Lawson (Richard Widmark) are implicitly pressured from higher powers to quickly complete the trial, and to not give a severe sentence in order to win over Germany’s support.

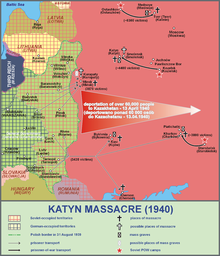

The defendants’ lawyer Rolfe (Maximilian Schell, who won the Academy Award for Best Actor with this movie) refutes the claims presented by Colonel Lawson, one after another, with sharp logic. Because Colonel Lawson has personal experience liberating a Nazi concentration camp, he wants to make sure the accused lawyers, who approved the documents to have Jews rounded up, are held fully accountable. Enraged, Rolfe refutes with, “What about the war responsibility of the Soviet Union that had the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression treaty with Germany, and illegally occupied and massacred under this treaty? What of the war responsibility for Great Britain’s Churchill, who agreed with Hitler in order to hold back communism?” With this, he voices the bitterness of Germans who silently endured the tyranny of the victorious nations in the Nuremberg Trials.

The defendants’ lawyer Rolfe (Maximilian Schell, who won the Academy Award for Best Actor with this movie) refutes the claims presented by Colonel Lawson, one after another, with sharp logic. Because Colonel Lawson has personal experience liberating a Nazi concentration camp, he wants to make sure the accused lawyers, who approved the documents to have Jews rounded up, are held fully accountable. Enraged, Rolfe refutes with, “What about the war responsibility of the Soviet Union that had the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression treaty with Germany, and illegally occupied and massacred under this treaty? What of the war responsibility for Great Britain’s Churchill, who agreed with Hitler in order to hold back communism?” With this, he voices the bitterness of Germans who silently endured the tyranny of the victorious nations in the Nuremberg Trials.

The greatest focus of the trial is whether Dr. Janning committed crimes under the Nuremberg Laws. The Nuremberg Laws were laws made by the Nazis, and defined relations between Jews and Germans as a crime. As a judge, Dr. Janning sentenced an old Jewish man to death on the charges of association with a young German girl Irene Hoffman (Judy Garland), and sentenced Irene to penal servitude for perjury when she denied the charges against the old man.

Judge Haywood, contrary to everyone’s prediction, passed a guilty verdict for all of the defendants, and he sentenced them all to life imprisonment. The basis of his sentence is that the prosecution proved “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the crimes were truly committed, and that, although the defendants did not commit the crimes directly, the crimes could not have occurred without the order of execution documents with the defendants’ names; thus, they are legal accomplices. Against Chief Judge Haywood’s judicial decision, the American judge serving as the trial’s deputy agrees with lawyer Rolfe’s argument, and refutes that the defendants were just abiding by the Nuremberg Laws—which were Germany’s national laws—and it would have been treason against the nation for the defendants to not abide by these laws.

There is also a pattern of conflicting interpretations between common law—preferred by Britain and America—and statutory law—preferred by Germany and France. Because Judge Haywood studied law in America that uses common law, he arrives at the guilty verdict based on the principles of case law that say precedent cases are the primary source of law for judgment, and that if there are previous similar trials, current verdicts are bound by precedent verdicts. Of course, since there is statutory law in Britain and America, when there is statutory law in the domain to judge, the stipulation is that statutory law takes preference over common law. Statutory laws have clear standards, and there are laws that have been used as the standards for a long period of time, such as the Napoleonic Code; however, what about the Nuremberg Laws? I think that the Nuremberg Laws suggest that a crazy leader can make crazy statutory laws. One can make a new law in America. However, that law must be approved by the majority in Congress, and it can be rejected by the Department of Justice if it opposes the Constitution.

Judge Haywood’s conviction disappoints both Germans and Americans. People believed that the defendants were only obeying the Nuremberg Laws, and it is the laws themselves that should be blamed. Also, there is disappointment because other trials happening around the same time generally found the defendants to be not guilty, and even if the defendants were found guilty, the sentence was very light. When Rolfe meets Judge Haywood face-to-face, he remarks, “In five years, the men you sentenced to life imprisonment will be free. In the near future, Americans may be placed in the situation where they are tried by the Soviet Army for injustice, so be warned,” and then leaves. Judge Haywood, when he meets with Dr. Janning in private upon Janning’s request, states, “You are guilty. The reason why is that you had already decided guilty before facing Irene Hoffman in court.” Also I think that, since Judge Haywood’s judicial decision becomes the precedent for future cases, he wanted to avoid his verdict from being cited to find future individuals who signed the death penalty for others as not guilty, as it could be if Judge Haywood had given an acquittal.

Marlene Dietrich performs as the widow of a general who was executed in the Nuremberg Trials. Her husband was found guilty in the Nuremberg Trials in what was like a lynching by the victorious nations immediately after the war, but the movie suggests the possibility that he may have been found innocent in a trial performed in1948. The widow tries to convey the spirits of German people to Judge Haywood, who she befriends, by telling him that both she and her husband hated Hitler, her husband had fought in order to protect the people of Germany, and most German people did not know of what the Nazis were doing.

Marlene Dietrich performs as the widow of a general who was executed in the Nuremberg Trials. Her husband was found guilty in the Nuremberg Trials in what was like a lynching by the victorious nations immediately after the war, but the movie suggests the possibility that he may have been found innocent in a trial performed in1948. The widow tries to convey the spirits of German people to Judge Haywood, who she befriends, by telling him that both she and her husband hated Hitler, her husband had fought in order to protect the people of Germany, and most German people did not know of what the Nazis were doing.

It is said that Marlene Dietrich’s life was the inspiration for the character of the general’s wife. After Marlene, a German woman, came to America, she and Jewish director Sternberg became a top Hollywood combo. Adolf Hitler liked Marlene and requested that she return to Germany, but Marlene who hated the Nazis refused, and in 1939, she acquired American citizenship; because of this, the screening of Dietrich’s movies was prohibited in Germany. During World War II, she repeatedly visited the American soldier frontline in order to give moral support.

Actress Setsuko Hara, who visited America after the war, said the following when she was introduced to Marlene Dietrich. “She looked so beautiful in her movies, but when I actually met Dietrich, she was a candid and casual person; her face was plain, and I didn’t feel that bewitching beauty seen in her movies. I didn’t get the impression of a beautiful person at all…”

I wonder if Marlene Dietrich’s beauty comes from her outstanding professionalism and determination in life. When Dietrich performs in this movie as the young and beautiful widow, she is already 60 years old. Of course Setsuko Hara suffered immense hardships during the war (like other Japanese people), but her words seem to not have much thought for how much Marlene Dietrich had to overcome.