This movie is about being a “young adult.” This is the period when people start thinking of themselves no longer as children, but aren’t yet recognized as adults by those around them; it is the period of their ego sprouting, selecting their life course, interest in the other gender, and conflict with grownups or the establishment. Similar to puberty, the period of young adulthood often includes behaviors such as becoming uncontrollable after leaving the supervision of their parents or acting without restraint in regards to violence or suicide, by obsessing over the opposite sex or drugs, or running away from home.

This movie is about being a “young adult.” This is the period when people start thinking of themselves no longer as children, but aren’t yet recognized as adults by those around them; it is the period of their ego sprouting, selecting their life course, interest in the other gender, and conflict with grownups or the establishment. Similar to puberty, the period of young adulthood often includes behaviors such as becoming uncontrollable after leaving the supervision of their parents or acting without restraint in regards to violence or suicide, by obsessing over the opposite sex or drugs, or running away from home.

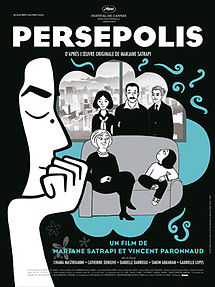

Persepolis is the film adaptation of the autobiographical graphic novel that depicts the period of young adulthood of Iranian graphic novelist Marjane Satrapi. Becoming an adult is quite difficult, but because her time of growth coincided completely with the Islamic Revolution of Iran, the Iran-Iraq War, and the subsequent cultural oppression, Persepolis is tinged with a considerable political flavor, though Marjane Satrapi is not a political person. She herself said this interesting comment: “I am not interested in politics. Politics is interested in ME!”

Marjane Satrapi was born in Tehran, Iran in 1969. She is the great grandchild of Ahmad Shah, the last shah of the former Qajar dynasty. Her grandfather and uncle were imprisoned for opposing the policies of Pahlavi Shah who succeeded Ahmad Shah. Her father also possessed progressive thoughts and he spearheaded a resistance movement with the majority of the nation against Pahlavi Shah who suppressed freedom. The joy of Pahlavi Shah fleeing the country in January of 1979 was short-lived; in April, Iran established the Islamic Republic based on a national referendum, Grand Ayatollah Khomeini took power, and oppression in Iran worsened beyond that under Pahlavi Shah’s reign. In addition, their neighbor Iraq, having had disputes at the national border for many years and fearing the influence of the Iranian Revolution, invaded Iran and the Iran-Iraq War began in 1980. Rumors of young soldiers being put in the frontline of the battlefield as a “bullet shield” circulated and many parents who had sons of drafting age fled the country.

In 1983, Marjane Satrapi’s parents arranged for her to move to Austria’s capital Vienna by herself to study abroad. It was not to avoid the war, but rather her parents feared their daughter might become a victim of legal rape; the minimum age for women to get married was reduced to 9 years old in the new Muslim regime and any sexual abuse after a young girl was forced to marry would no longer be considered a crime. However, she was not able to adapt to life in Austria. In those days, the international image of Iranians was a cruel savage, and she wondered if others saw her this way. In addition, she struggled with how her looks and body were different than European girls at an age when she was self-conscious about her appearance; she lived a depraved life without the supervision of her parents, fought with the people providing her housing, and, in the end, slept in the streets without a house to live in and spent her days digging through dumpsters. Suffering from pneumonia and homesick from such a lifestyle, she finally returned to Iran.

In 1983, Marjane Satrapi’s parents arranged for her to move to Austria’s capital Vienna by herself to study abroad. It was not to avoid the war, but rather her parents feared their daughter might become a victim of legal rape; the minimum age for women to get married was reduced to 9 years old in the new Muslim regime and any sexual abuse after a young girl was forced to marry would no longer be considered a crime. However, she was not able to adapt to life in Austria. In those days, the international image of Iranians was a cruel savage, and she wondered if others saw her this way. In addition, she struggled with how her looks and body were different than European girls at an age when she was self-conscious about her appearance; she lived a depraved life without the supervision of her parents, fought with the people providing her housing, and, in the end, slept in the streets without a house to live in and spent her days digging through dumpsters. Suffering from pneumonia and homesick from such a lifestyle, she finally returned to Iran.

After returning home, she became depressed and she almost died from overdosing on drugs. However, with the encouraging words of her family–“Study at a university and become an independent woman”—she entered university. After the failure of a brief marriage with a young Iranian man, the movie ends with her moving to France in 1994 at the suggestion of her parents—“You can’t live your potential in present-day Iran.”

Her uncle was executed under the Islamic Republic alongside other liberals and socialists. A friend that went to war returned without limbs. A friend who lived next door was hit by a missile from Iraq and died. Parties were illegal under the Islamic Republic, but she dared to participate and a friend was chased by the police and died. She was arrested for behavior unsuitable for an Islamic woman and was told, “A fine or a beating?”; she was released after paying a large sum of money. The university she entered with high expectations was governed by Islamic principle, so she had no joy. She had thought Pahlavi Shah was a bad person, but his regime imprisoned her uncle while the regime of the Muslim Khomeini executed her uncle. Nothing in society had improved.

Even though this movie depicts her terrible youth, it does not lose its peculiar cheerfulness. One reason for its cheerfulness is that it is animated and not performed by real actors. Her drawings render a strange, humorous style. However, the brightness flowing through the bottom of this movie will come from the love of family. Marjane Satrapi’s parents were progressive people, but unlike her grandfather and uncle that were executed, they acquired worldly wisdom in order to find a way to survive under political and religious oppression. However, at the same time, they taught their daughter to do the right thing in life, to skillfully find happiness, and to believe in and pursue her own talents. They made up their minds to protect their child from danger by any means and unconditionally forgave and supported her completely if she made a mistake because of immaturity.

Even though this movie depicts her terrible youth, it does not lose its peculiar cheerfulness. One reason for its cheerfulness is that it is animated and not performed by real actors. Her drawings render a strange, humorous style. However, the brightness flowing through the bottom of this movie will come from the love of family. Marjane Satrapi’s parents were progressive people, but unlike her grandfather and uncle that were executed, they acquired worldly wisdom in order to find a way to survive under political and religious oppression. However, at the same time, they taught their daughter to do the right thing in life, to skillfully find happiness, and to believe in and pursue her own talents. They made up their minds to protect their child from danger by any means and unconditionally forgave and supported her completely if she made a mistake because of immaturity.

With the genuine support from her parents and grandmother, Marjane Satrapi grew up to be a real adult. She was a child who had strong curiosity, was outspoken with her thoughts—which made people around her worry—and became depressed from her difficulties to the point where she may not have been able to recover; but she was also surprisingly acute enough to see opportunities and was able to size up her surroundings with a watchful eye in order to survive. As soon as she was determined to not lose sleep over what was already past, she became a strong person who was amazingly able to live facing forward. Though she was a loser in Austria, she blossomed in a big way in France. Was there a difference in Austria and France? Or is the reason that she became a real adult in France?